Forward-looking: We often hear about new battery tech being researched – but not released – that could store more energy, charge faster, or last longer before its capacity deteriorates. However, it's easy to lose sight of the greater picture, where lithium-ion batteries have become significantly cheaper to produce even when compared to a decade ago.

Consumers often lament that battery technology hasn't improved at the same rate as others, like computing power which has gone up dramatically over the last few decades while batteries have only improved in relatively smaller steps. However, the biggest issue we face today is that with the proliferation of mobile devices, electric cars, and grid storage solutions, we simply can't make enough batteries to meet demand.

One factor in that equation is price, which is directly related to the materials required to make them. The most expensive of those materials go into the cathode – lithium, nickel, manganese, and cobalt, depending on the battery chemistry. There's also the issue of longevity, which ranges from a few hundred charge cycles up to a few thousand, with no clear path to improvement unless we're willing to compromise on charging speed and energy density.

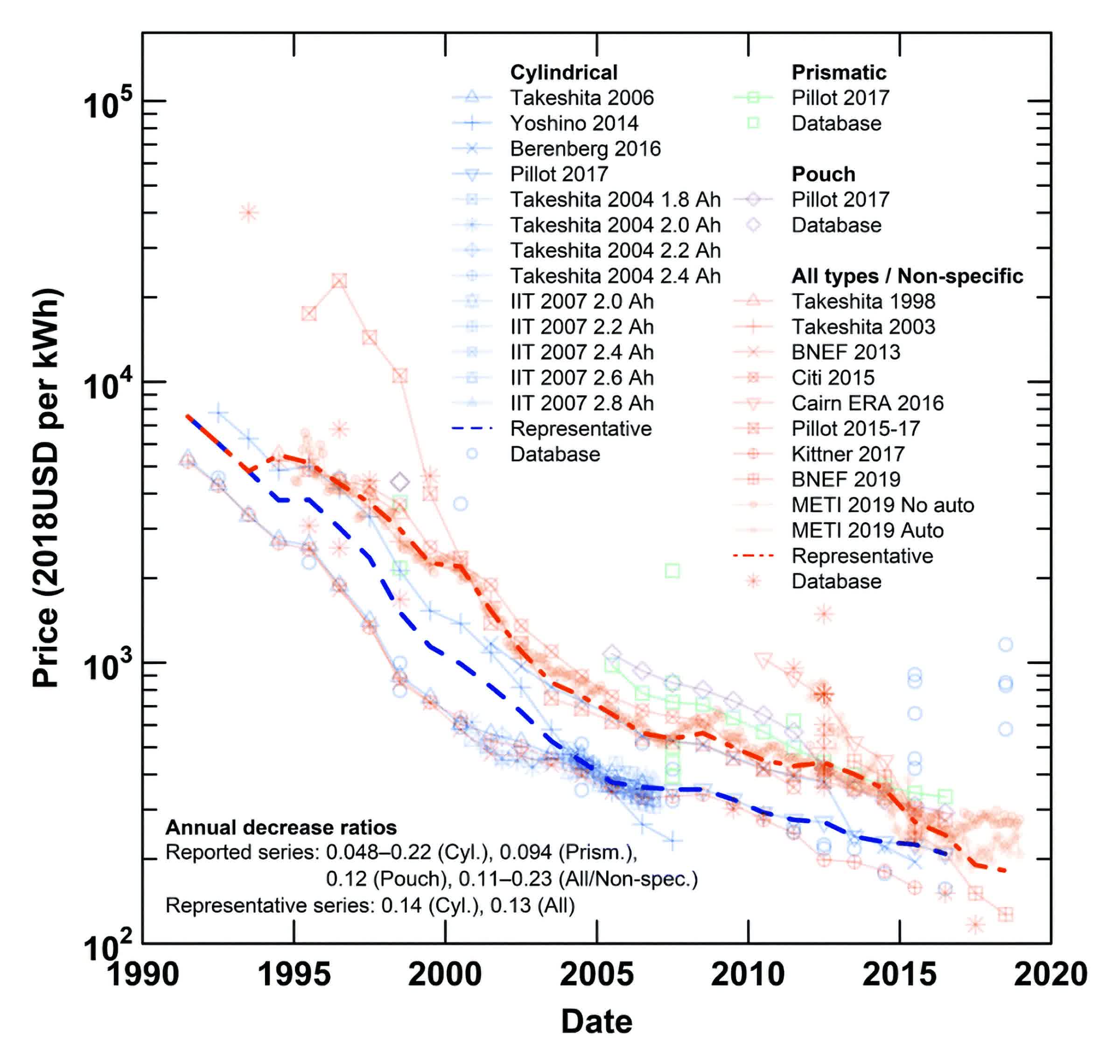

According to new analysis by MIT researchers, the overall cost of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries has fallen dramatically over the last 30 years however. It's fallen by 97 percent since the commercial introduction of the lithium-ion design, which is a comparable drop to that of the cost of photovoltaic cells used in solar panels.

But more importantly, the price decline was faster than previously estimated, which could explain why many automakers have started producing electric vehicles. Some like Volkswagen are also scrambling to build battery factories and experiment with new battery formats.

Most published work on the subject of cost reduction in lithium battery cells had typically produced conflicting results, and some didn't take into account weight and volume improvements. When adding those parameters in, the natural conclusion is that lithium-ion technology was adopted not necessarily because it was cheaper than the alternatives, but because it paved the way for portable devices, electric vehicles with an adequate driving range, and grid storage solutions for surplus solar and wind energy.

The researchers point out the findings are not just a matter of "retracing the history of battery development," but could also paint a clearer picture of its trajectory and how much potential there is to further improve and reduce the cost of lithium-ion technologies. This lends some credibility to Elon Musk's claim that the 2170 lithium-ion cells made by Panasonic for Tesla Model 3 and Model Y cars could see energy density improvements of 50 percent or higher in the next five years.

As for pricing, lithium-ion battery packs cost $1,183 per kilowatt hour in 2010, which dropped to $137 per kilowatt hour in 2020. Many analysts believe mass adoption of electric vehicles will be greatly influenced by how quickly the cost of batteries can dip below the $100 threshold.

The most optimistic view is that this could happen by 2025, when global lithium-ion battery production capacity will have tripled and price per kilowatt hour will have dropped to $93.