The big picture: Japan's share of global semiconductor sales has gone from 50 percent in 1988 to less than 10 percent today. The country has more chip factories than any other country – 84 to be exact – but only a few of them use advanced sub-10nm process nodes. This is why the country is scrambling to reignite its semiconductor industry, even if it comes at an incredibly high cost over the next decade.

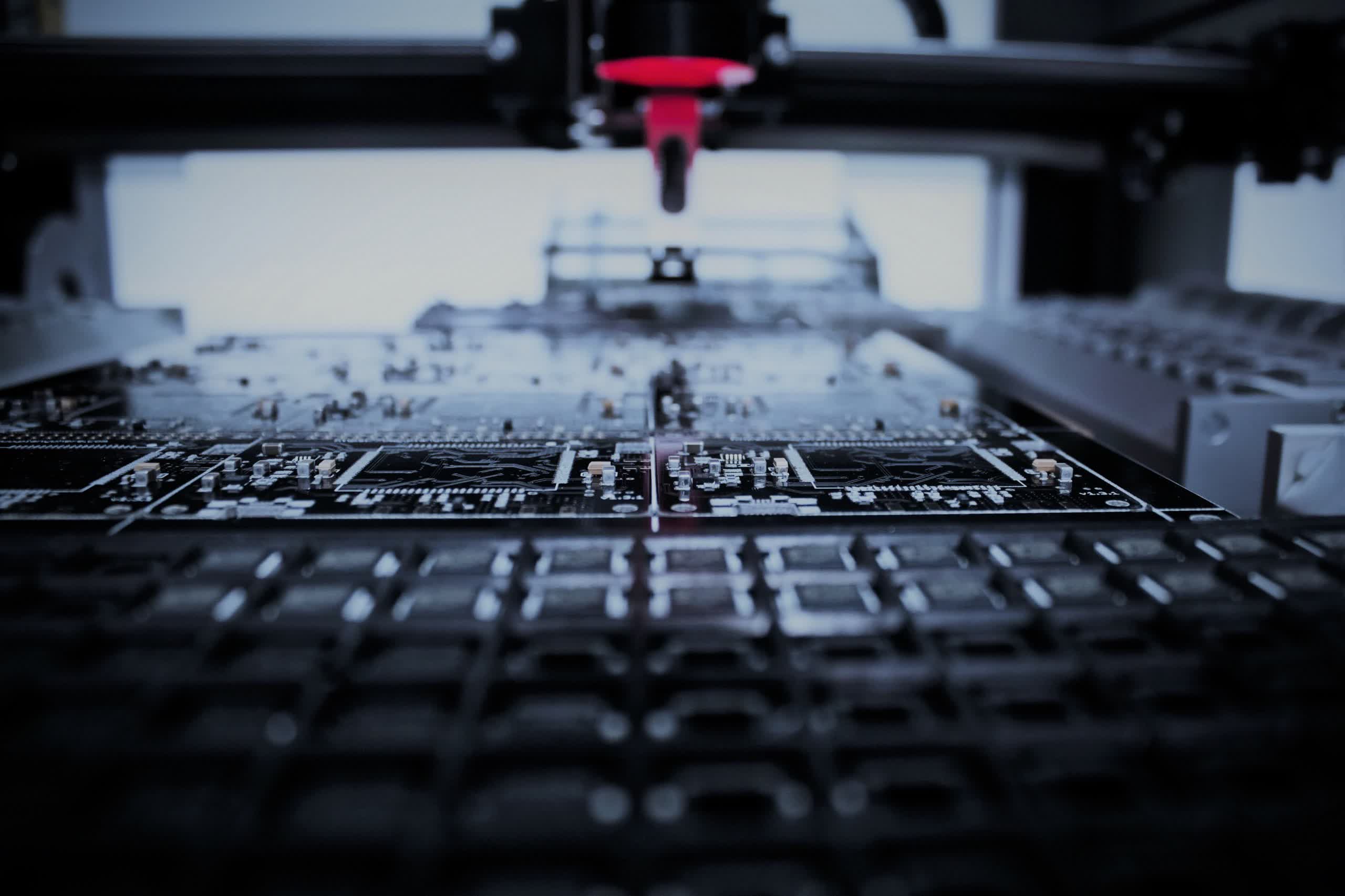

The ongoing chip shortage has affected everything from LCD displays to graphics cards, game consoles, TVs, and even automakers. For consumers, this has created a hostile buying environment in some instances, while some governments have become acutely aware of the fragility of the global tech supply chain.

In the US, the Biden administration is trying to fix the situation by committing $52 billion towards boosting the local semiconductor industry, heeding the call of the Silicon Industry Association but at the same time falling short of the $100 billion that China is pouring into government subsidies for semiconductor companies.

The European Union is also looking to double down on chip manufacturing as part of its "Digital Compass" initiative, which is meant to increase the region's share in the global semiconductor manufacturing to 20 percent by 2030. It's an overambitious goal, but Intel has promised to build a chip factory in Europe, while Apple will invest $1.2 billion in a silicon design center in Germany that will focus on 5G and other wireless connectivity technologies.

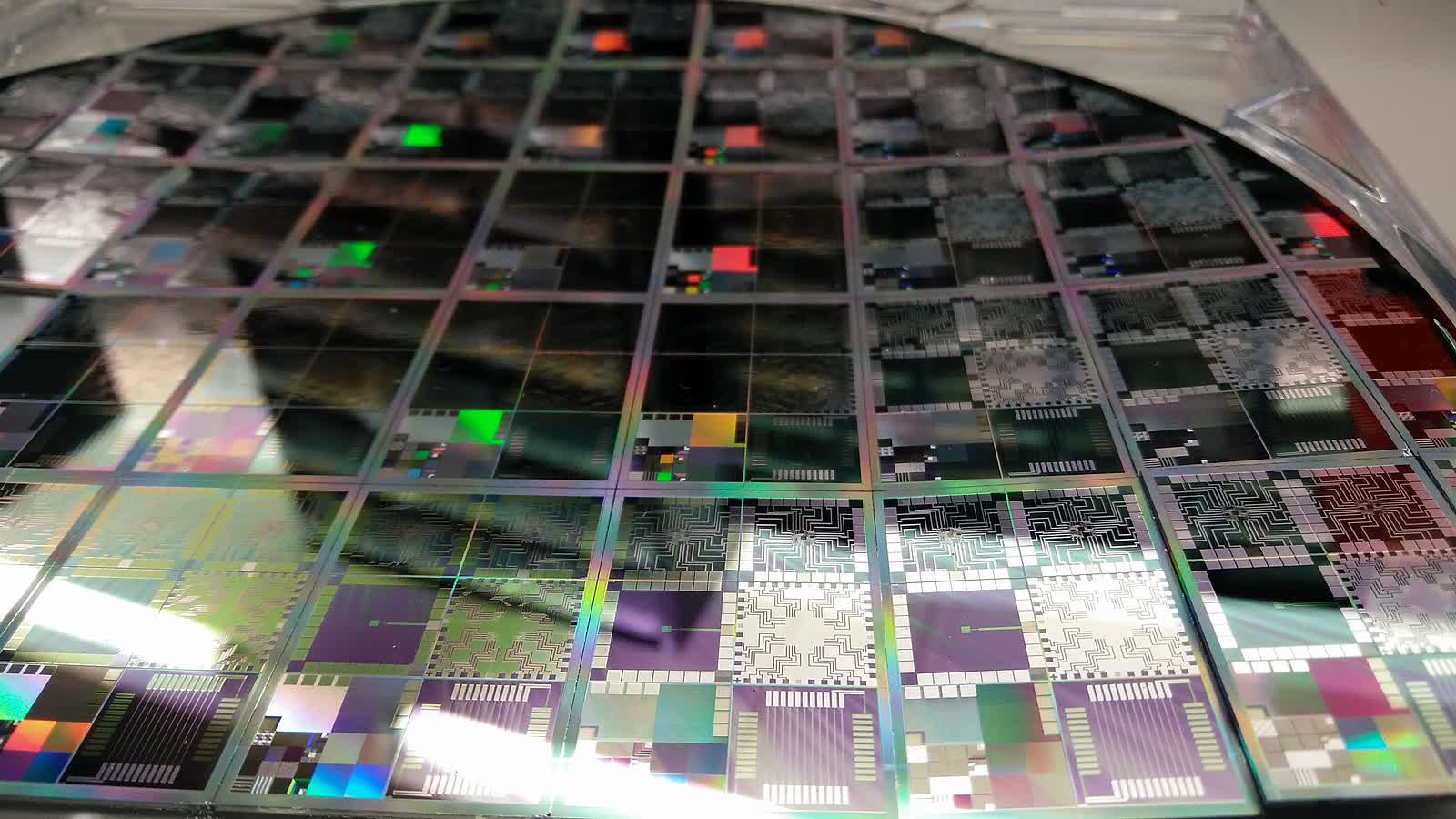

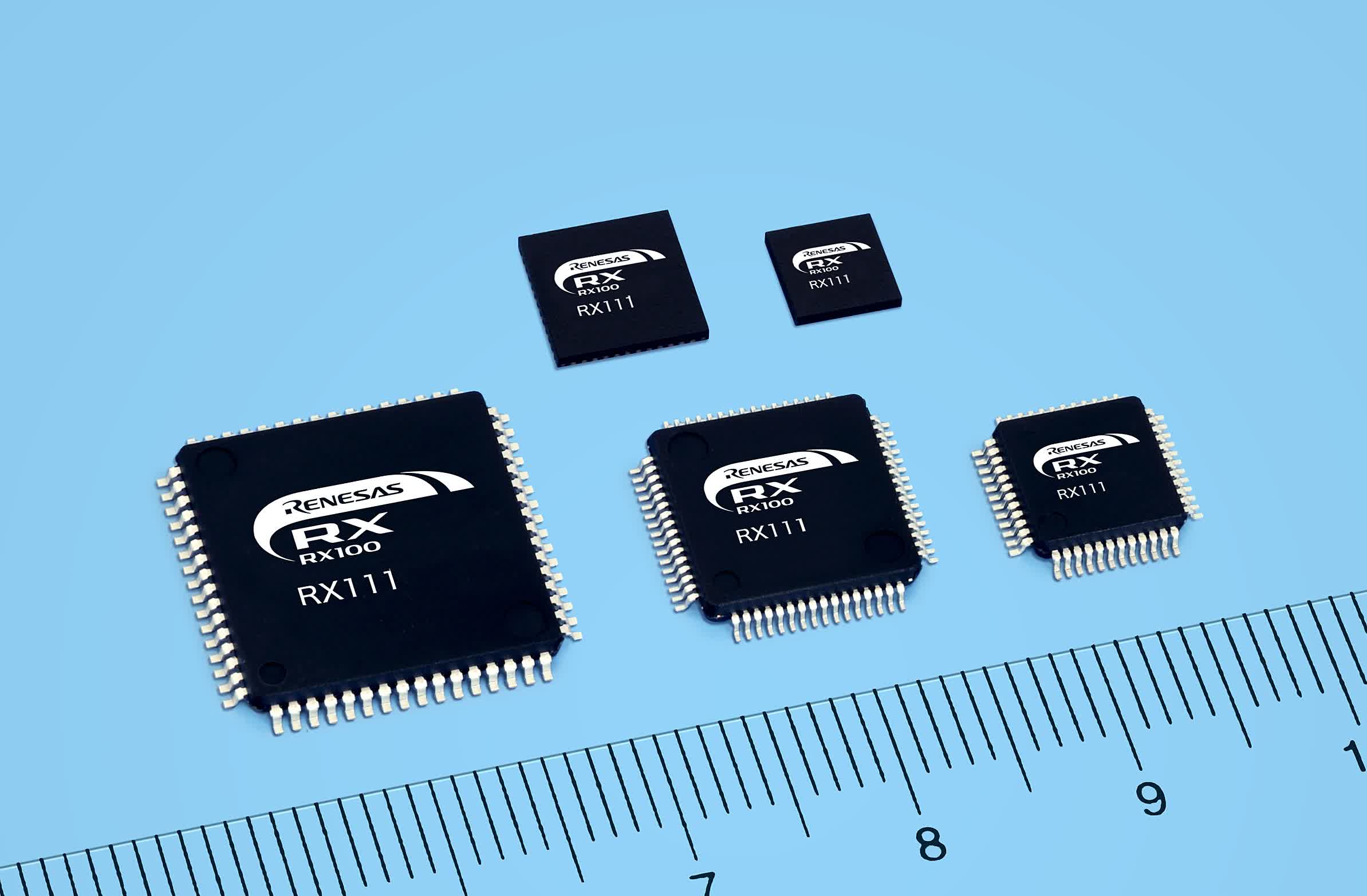

Meanwhile in Japan, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga revealed his country has made it a priority to save the local semiconductor industry from falling apart and help it regain its legs when it comes to advanced manufacturing processes. An interesting but little-known fact is that Japan has no less than 84 semiconductor plants – more than any other country and around eight times more than Taiwan, or four times more than South Korea.

The main issue with these plants is most of them are using old, out-of-date equipment, some of which was offloaded earlier this year to Chinese companies that were more than happy to purchase it to go around US restrictions. The only notable exceptions are Sony and Kioxia, who are well-known for their advanced camera sensors and flash memory, respectively.

Although you'd think Japan's goal is to increase its output of semiconductors at all costs, the country's plan is more about "national security." Specifically, it wants to create an attractive environment for companies like TSMC to build local foundries and research and development centers, with the ultimate goal of carving an independent path for infusing its infrastructure with future technologies.

This strategy is no doubt born from simple observations on how global tensions and the race to achieve technological dominance have affected the global tech supply chain, and also led to a step back from the globalization of the chip industry.

On top of that, Japan went from dominating global semiconductor sales in 1988 to importing 64 percent of the chips needed for its local industry last year.

Japan also wants to implement stricter export controls for chips as well as materials needed to make them, especially as they're considered a sensitive industry that enables the manufacturing of equipment for both civilian and military use.

The big question, however, is what it will take for Japan to achieve this goal. According to Tetsuro Higashi, who is the former chairman of Tokyo Electron, the initial investment is at least one trillion yen ($9 billion), with trillions more over the next ten years. The 71-year-old silicon industry veteran says it will also take a combination of subsidies, tax breaks, and a new framework to facilitate technology sharing.