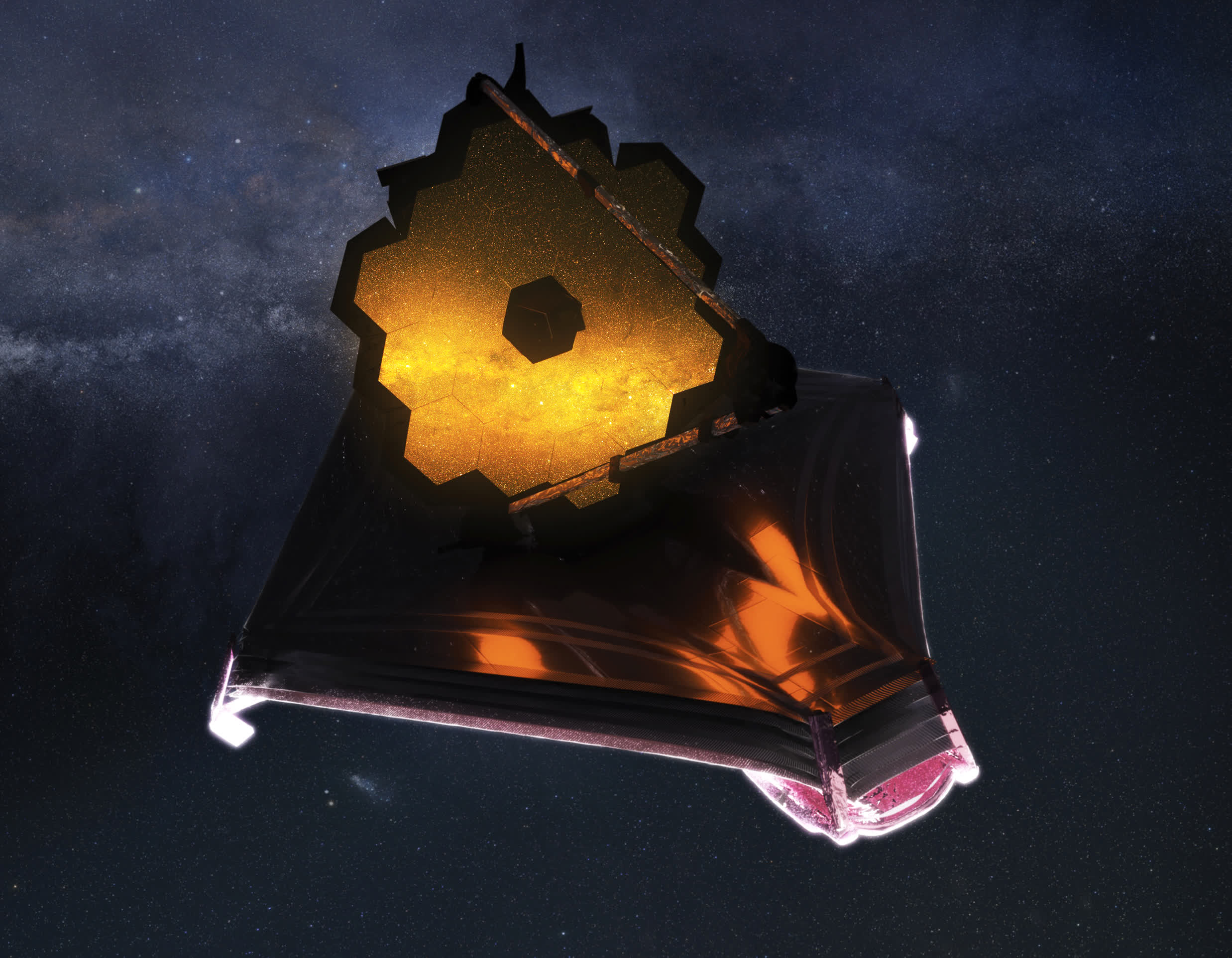

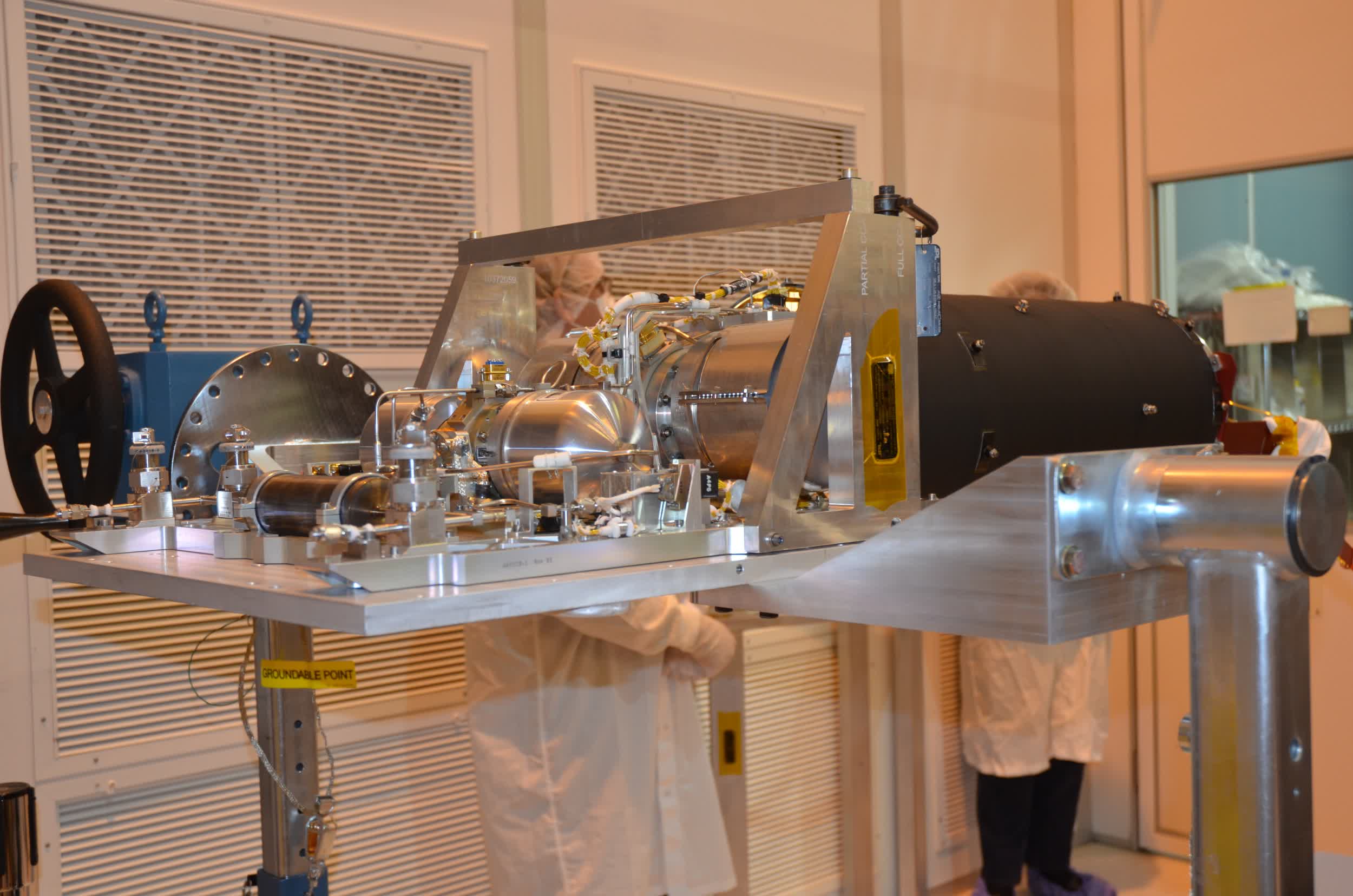

In brief: The James Webb Space Telescope recently passed a challenging milestone as it continues preparations for scientific missions later this year. The instruments have been passively cooling in the shade of its giant sunshield for the past few months, but one of its key components - the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) - needs to be even colder than what the dark of space can achieve by itself in order to detect longer infrared wavelengths.

To help MIRI reach its target operating temperature, engineers developed an electrically powered cryocooler. When activated, the system is able to bring the instrument down to its final operating temperature below 7 kelvins (minus 447 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 266 degrees Celsius).

On April 7, MIRI successfully achieved its final operating temperature.

"The team was both excited and nervous going into the critical activity. In the end it was a textbook execution of the procedure, and the cooler performance is even better than expected," said Analyn Schneider, project manager for MIRI at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

"We spent years practicing for that moment, running through the commands and the checks that we did on MIRI," said Mike Ressler, project scientist for MIRI at JPL. "It was kind of like a movie script: Everything we were supposed to do was written down and rehearsed. When the test data rolled in, I was ecstatic to see it looked exactly as expected and that we have a healthy instrument."

With the instrument now at the correct temperature, team members can start capturing sample photos of stars and other known objects to help calibrate the device alongside preparations for the scope's other three instruments: the near-infrared camera (NIRCam), the near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec) and the fine guidance sensor / near infrared imager and slitless spectrograph (FGS/NIRISS).

Webb's first science images are expected to be released this summer.