Justice served: A judge has told the co-founder of the sham copyright-trolling law firm Prenda Law that he cannot continue filing piracy lawsuits from his jail cell. It seems like a no-brainer, but the lawyer's ultimate point is to make the case that the laws holding him in prison are "unconstitutional," so he should be released.

Disgraced Prenda Law attorney Paul Hansmeier is serving a 14-year sentence for running a copyright entrapment scam, which he pled guilty to in 2018. Since then, he has filed multiple legal actions from his jail cell to get out of serving his time.

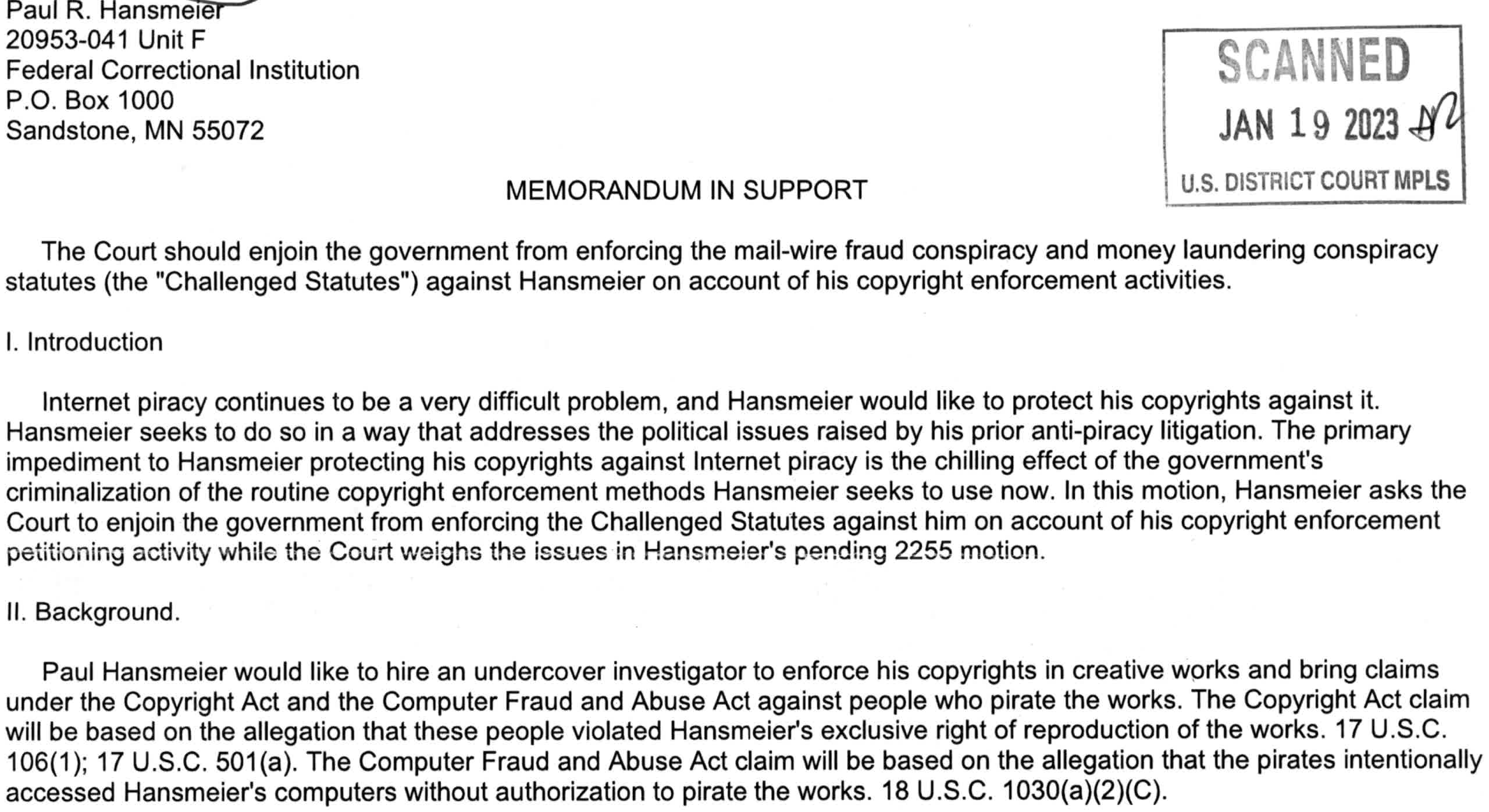

Hansmeier's latest ploy was to file a motion with the US District Court in Minnesota, the same court that convicted him, asking for a preliminary injunction against the government from enforcing fraud and money laundering statutes against him. The stated purpose is to allow him to continue filing copyright infringement cases while incarcerated, employing a private investigator to do the legwork.

Of course, this is what landed him in prison in the first place. Essentially he is asking that the court not allow his conviction, which is under appeal, to prevent him from protecting his and his clients' copyrights.

Hansmeier founded Prenda with John Steele, and together they set up a business model of settling bogus copyright claims for around $3,000. Up until 2013, Prenda Law would upload pornographic videos to sites like The Pirate Bay, then sue the thousands of people that downloaded the content.

Hansmeier's six-page motion promises his future lawsuits will not be on the same scale, nor will they involve pornography. Instead, he suggests he will pursue a smaller number of clients and litigate against people "pirating" material such as "poetry." He claims that failure to provide injunctive relief violates his First Amendment rights.

"Hansmeier is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of injunctive relief because Hansmeier has lost his First Amendment freedoms. Specifically, Hansmeier is chilled from engaging in First Amendment-protected activity. Hansmeier's proposed copyright enforcement activity is protected by the First Amendment's Petition Clause, which 'protects the rights of individuals to appeal to courts and other forums established by the government for resolution of legal disputes.'"

While there is no law preventing an inmate from filing a lawsuit of any kind from prison, there are apparent misgivings about allowing Hansmeier to continue to conduct his business, considering the nature of his conviction. It only took the District Court one paragraph to say "no" under the legal precedent of Devose v. Herrington, 1994.

After summarizing and restating Hansmeier's request, Judge Joan N. Ericksen said, "Defendant's motion for a preliminary injunction [Docket No. 270] is DENIED. IT IS SO ORDERED [emphasis hers].

Hansmeier has filed no fewer than 16 motions to the court as he waits for an appeal hearing, including asking for a reduced sentence (two years) for alleged mistreatment while in jail. In that one, he claimed that jailers had locked him in solitary confinement for five months, limited him to only one phone call to his family per month, withheld the newspaper from him, and did not allow him attorney-client privileged calls. That petition was also denied.