The big picture: Sanctions imposed by the US and its allies on Chinese companies have already produced changes in the global supply chain, and more are likely to come. However, the CHIPS Act adds another layer of uncertainty for global players like TSMC, Samsung, and even American companies like Intel and Micron who also operate some facilities in China but wish to secure government subsidies for their expansion plans. The obvious loser here is the Chinese semiconductor industry, which will need to find new ways to survive in a rough geopolitical climate.

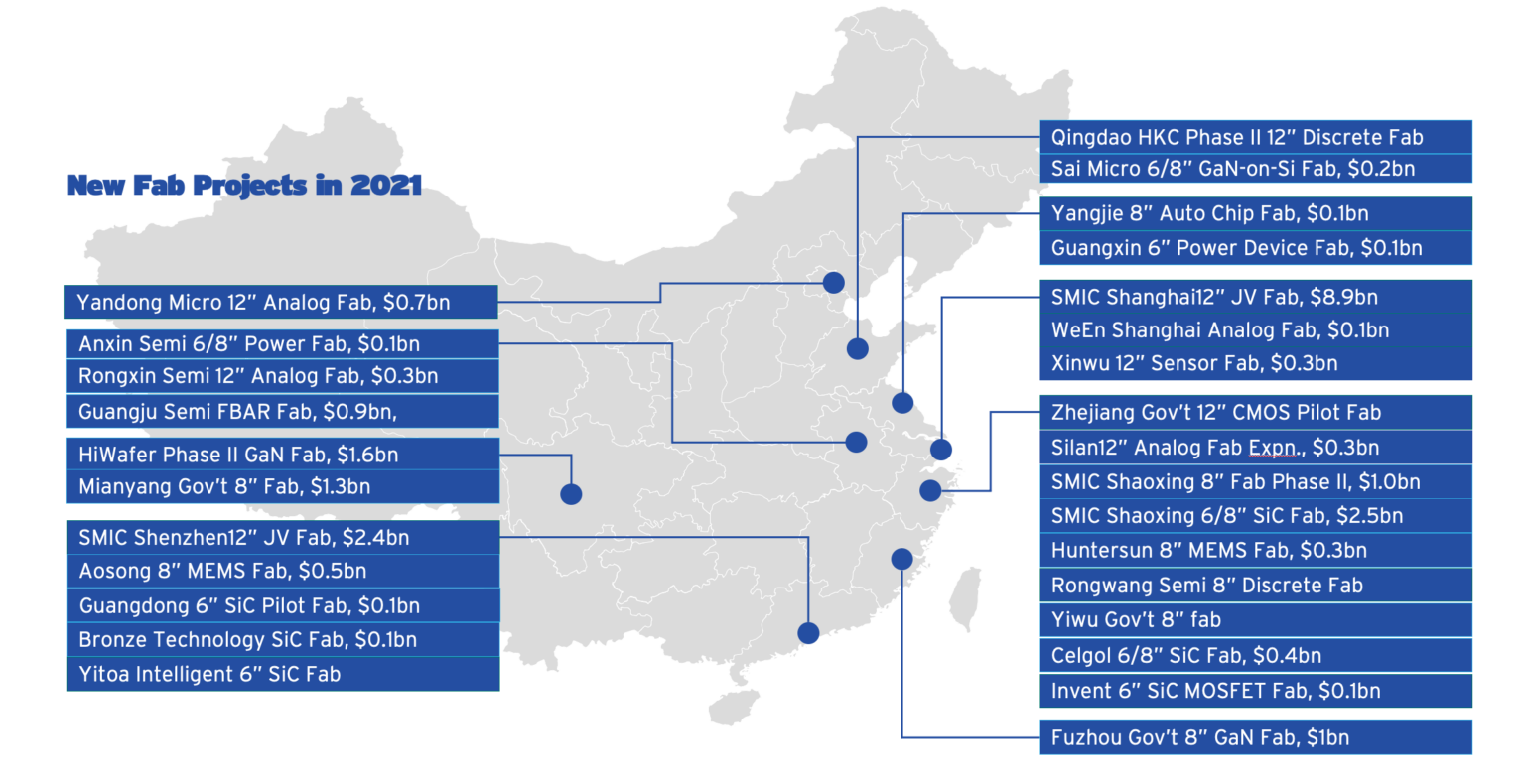

Back in 2021, we learned that companies like SMIC and China's Yangtze Memory Technologies Co (YMTC) had made incredible progress in catching up with global players in the semiconductor industry, at least when it comes to the manufacturing of NAND, RAM, and low-end CPUs and GPUs.

In the case of YMTC, it even developed an advanced hybrid bonding technology for stacking memory dies that enabled local SSD manufacturers to come up with products that were quite competitive in terms of storage density and performance with mainstream offerings from the likes of Samsung, Micron, and SK Hynix. It was enough to pique Apple's interest for a short while as YMTC seemed like a potential alternative supplier of NAND memory for lower-end iPhones.

What surprised industry watchers was the fast pace of Chinese semiconductor developments in all areas except high-end GPUs for gaming and AI accelerators for the data center. Advanced foundries were being built using billions in government-backed funding, and companies like SMIC, Wingtech, Zhaoxin, Starblaze Technology, and Tongfu Microelectronics were poaching talent from Taiwan.

That said, the US-China trade war that started under the Trump Administration several years ago has continued under President Biden and resulted in several sanctions and import restrictions for tech produced in China. This has slowed down the latter country's ambitions somewhat and made procuring cutting-edge manufacturing equipment an arduous task.

Although the Biden Administration has allowed some US citizens to continue working for Chinese semiconductor companies that are on the Entity List, those organizations have opted to drive away those employees as part of a bizarre "de-Americanization" effort. The effects of that decision are still unclear, but there's a bigger problem looming for all companies that operate fabs or research and development centers in China – the CHIPS Act.

Image: President Biden holding a wafer | AP News

China has already lost easy access to purchase or license critical US-made technologies, and companies that operate in the region will have to decide whether or not it's in their best interest to continue doing so in the future. Many semiconductor companies want to tap into the large funding pool of the CHIPS Act, but one key requirement is that they aren't allowed to partner up with Chinese companies or expand their manufacturing capacity in the region for a decade.

Analysts at TrendForce believe this will have a significant impact on Chinese foundries, silicon wafer manufacturers, and memory makers for the next 10 years. Couple that with Japanese and Dutch manufacturers agreeing to aid in export controls against China even when it comes to older, DUV equipment for more mature process nodes, and you can easily see how the country's plan to achieve technological self-sufficiency by 2025 seems destined for failure.

Also read: China's supply chain: Shenzhen wasn't built in a day

A particularly sore spot in the forecast is China's share of global DRAM output, which is projected to drop from 14 percent in 2023 to just 12 percent in 2025. NAND output might see an even bigger drop from 31 percent to 18 percent over the next two years. American companies like Intel and Micron as well as Korean companies such as Samsung and SK Hynix will want to cover the resulting gap, but they won't be able to use their Chinese facilities to do so.

If they receive CHIPS Act funding, they won't be able to upgrade assembly lines or build additional capacity, meaning their Chinese operations will get scaled down over time as chips made in the region become less competitive with alternatives on the global market.

TSMC faces a similar conundrum with its Fab 16 in Nanjing, China. The facility mostly produces chips on a 28 nm process node and plans to upgrade assembly lines to a 16 nm process node are likely to get delayed or scrapped entirely. Nevertheless, smaller Taiwanese foundries like VIS and PSMC that focus on chips for automotive applications are already benefiting from more orders coming their way.

TrendForce says American companies have already reduced their manufacturing output in China and are looking for ways to shift production elsewhere. It's also possible that some will opt for a strategy to split their production efforts, with Chinese factories covering local demand and facilities outside the country serving other regions.

Some like TSMC founder Morris Chang believe all this will lead to chip industry fragmentation, increased costs, and a slowdown of innovation, though he agrees with most US sanctions against China. Advanced chip factories take several years to get up and running, and the US won't see the effects of its foreign policy until then. Still, it has already managed to drive private investments totaling $200 billion into US-based chip manufacturing.

Meanwhile, China's chip industry is preparing a concerted reaction to what it sees as a significant blow to its recovery efforts. Last month, Huawei chairman Eric Xu said the Chinese semiconductor industry will soon be "reborn" as a result of the many sanctions that have been levied against it. Xu claims a consortium of Chinese companies (including Huawei) has already developed the necessary equipment for a 14 nm process node, which is still several generations behind the global industry but a significant step for the local one.

Separately, the local government of China's southern Guangdong province is investing no less than 30 billion yuan (around $4.36 billion) to accelerate startups specializing in materials science and equipment for the manufacturing of chips for automotive applications.

For now, it looks like China's semiconductor industry could remain frozen in time despite all the billions being thrown at it by its government in hopes of making it less reliant on American-made technology. It's only capable of producing 14 nm logic chips, 18 nm DRAM, and 128-layer 3D NAND – something that won't change as long as US concerns about China using advanced semiconductors for military purposes persist.